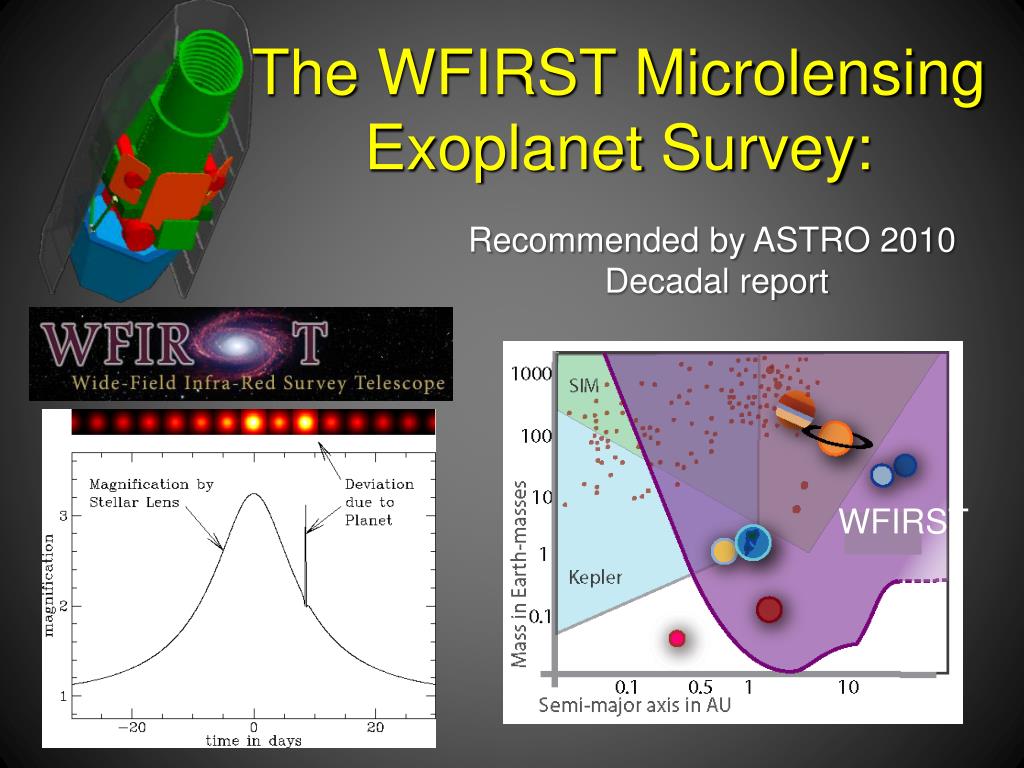

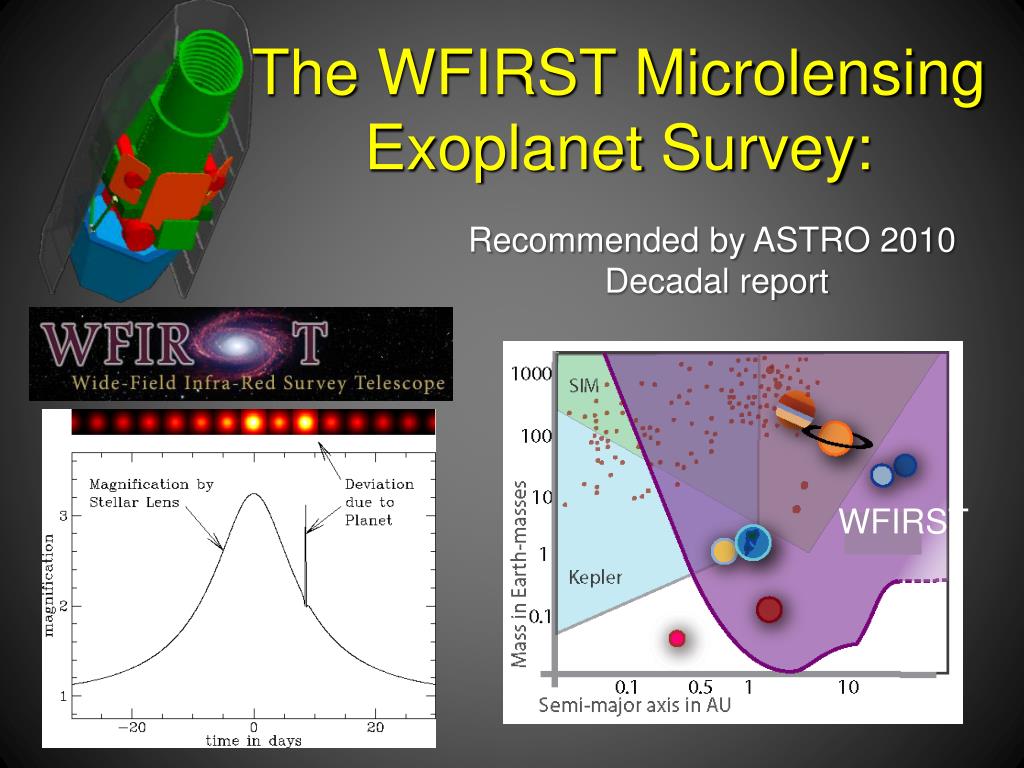

Its combination of aperture, field-of-view, and NIR (H4RG) detectors are essentially optimal for this purpose. Mentation needed to carry out the microlensing survey that enables a more complete statistical census of exoplanets in the galactic bulge. The WFIRST mission ( Spergel et al., 2015) provides a nearly ideal architecture with the nearly ideal instru.

Given that M dwarfs emit the majority of their light in the NIR, given that the galactic bulge is generally heavily extincted, and given that the sky is very bright in the NIR from the ground, NIR surveys from space are optimal for microlensing surveys for exoplanets. The smallest sources in the galactic bulge, M dwarfs, enable the detection of planets with mass as low as that of roughly 2 times the mass of the Moon.

The ultimate limit to the mass of a planet that can be detected via microlensing is set by the angular size of the source. Once this resolution is achieved, it is possible to estimate the mass of the lens and the source for the majority of microlensing events ( Bennett et al., 2006). Given the crowded conditions of the galactic bulge, resolving the lens and source from unrelated background stars requires resolutions of <0.3 arcsecond. These perturbations are also stochastic, and thus require continuous monitoring of the microlensing events, at least ~15 minutes. The perturbations of these microlensing events last from an hour to a few days, and have probabilities (given the existence of planet) of less than a few percent to tens of percent (for planets with the mass of the Moon to the mass Jupiter). Thus, microlensing surveys require monitoring a few square degrees with a resolution of <0.3 arcsecond on time scales of a few days or less. The only line of sight where this is possible given current technology is the galactic bulge, where the stellar surface density is approximately 20 million stars per square degree down to magnitudes of H AB ≅ 21. Microlensing events due to stellar lenses, which last a few days to hundreds of days, are both stochastic and rare, and thus require simultaneous monitoring of hundreds of millions of stars in order to detect a few thousand microlensing events. Rather, to enable these capabilities, a space-based, near-infrared (NIR) mission with a relatively large field of view is required ( Bennett and Rhie, 2002), for several reasons:

The ultimate limit to the mass of a planet that can be detected via microlensing is set by the angular size of the source. Once this resolution is achieved, it is possible to estimate the mass of the lens and the source for the majority of microlensing events ( Bennett et al., 2006). Given the crowded conditions of the galactic bulge, resolving the lens and source from unrelated background stars requires resolutions of <0.3 arcsecond. These perturbations are also stochastic, and thus require continuous monitoring of the microlensing events, at least ~15 minutes. The perturbations of these microlensing events last from an hour to a few days, and have probabilities (given the existence of planet) of less than a few percent to tens of percent (for planets with the mass of the Moon to the mass Jupiter). Thus, microlensing surveys require monitoring a few square degrees with a resolution of <0.3 arcsecond on time scales of a few days or less. The only line of sight where this is possible given current technology is the galactic bulge, where the stellar surface density is approximately 20 million stars per square degree down to magnitudes of H AB ≅ 21. Microlensing events due to stellar lenses, which last a few days to hundreds of days, are both stochastic and rare, and thus require simultaneous monitoring of hundreds of millions of stars in order to detect a few thousand microlensing events. Rather, to enable these capabilities, a space-based, near-infrared (NIR) mission with a relatively large field of view is required ( Bennett and Rhie, 2002), for several reasons: #Telescope glimpses population freefloating planets full#

However, it is not possible to achieve this full potential of the microlensing technique from the ground. It is therefore naturally complementary to the transit technique.

Implementing the Exoplanet Science Strategy EXPANDING THE STATISTICAL CENSUS OF EXOPLANETS IN THE GALAXYĪs described in Chapter 2, although radial velocity (RV), direct imaging, and astrometry are all, in principle, sensitive to long-period planets, the microlensing technique is uniquely sensitive to low-mass planets at large separations-in particular, very low-mass (mass greater than roughly two times the mass of the Moon) planets in orbits greater than roughly 1 AU-and analogues of the Solar System ice giants.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)